BAIL Yourself Out Happy Hour

Hosted by entrepreneur and corporate culture strategist Kandice Whitaker, the Bail Yourself Out Happy Hour Podcast blends insightful career discussions with the laid-back vibe of a post-work gathering. Each episode dives into real-world business challenges, personal growth stories, and expert strategies for professional success.

From career pivots and entrepreneurial journeys to leadership development and navigating workplace dynamics, Kandice and her guests share actionable advice, industry secrets, and inspiring stories. With its unique mix of power-lunch energy and happy-hour candor, Bail Yourself Out is the ultimate podcast for ambitious professionals ready to take charge, level up, and thrive in their careers.

BAIL Yourself Out Happy Hour

HBCU vs PWI

Use Left/Right to seek, Home/End to jump to start or end. Hold shift to jump forward or backward.

The new Bail Yourself Out podcast is hosted by Kandice Whitaker, a successful entrepreneur, and specialist in navigating corporate culture. With a fresh new approach to maximizing optimal career moves - the Bail Yourself Out podcast is where the power lunch and the after-work happy hour intersect for dynamic business discussions in a relaxed atmosphere.

Follow us @BAILYourselfOut

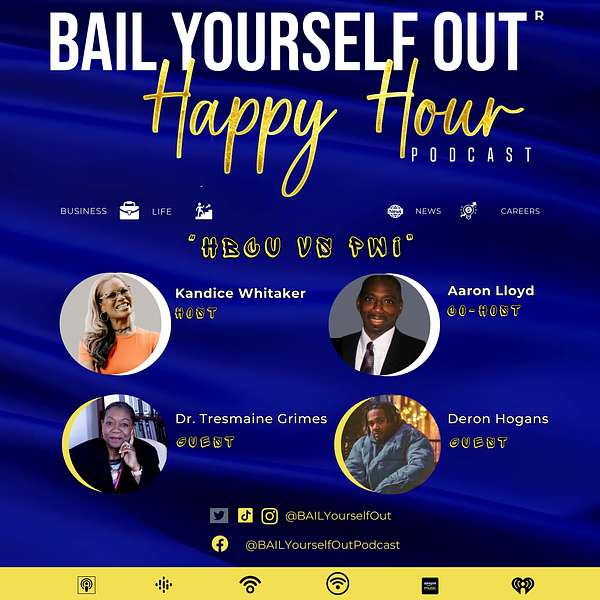

Season 2 Episode 10 - "HBCU vs PWI"

Guest Co-Host - Aaron Lloyd

Guests - Dr. Tresmaine Grimes and Deron Hogans

Keep up with Kandice Whitaker and the BAIL Yourself Out Community Online

www.linktr.ee/bailyourselfoutpod

© 2023 Alpha and Omega Consulting Inc. All rights reserved.

Hey y'all Hey welcome to the happy hour lounge. This is your girl Kandice with the K. I am so super excited about today's episode today we are going to talk about historically black colleges and universities versus predominantly white institutions. In today's lounge. I got my guest co host Aaron Lloyd. Y'all know him, but our guests y'all. I have two wonderful guests Dr. Tresmaine Grimes who is a dean at Pace University, but y'all she is also reppin the Yale Bulldogs, South Carolina State Bulldogs and Columbia University. Welcome to the lounge, Dr. Grimes. And then our old friend I know y'all remember him from season one. My homie Duran Hogans, who's a researcher. And he's reppin Hampton University, the other Hu and Georgetown. Love y'all. Thank you so much for joining our conversation today. So I'm going to start right here with how did your experience at college impact your view of the world, both of you have the very interesting experiences of having historically black college peer review and also predominantly white.

Dr. Tresmaine Grimes:So because I'm loquacious, I'll go ahead and start. I think that going to college going to Yale, actually, was not what I anticipated. Because I did not anticipate that it would be there that I would get to understand black culture. More than in Harlem, where I was raised, because in Harlem, you could take things for granted. Okay,

Kandice Whitaker:shout out to Harlem, USA uptown baby, let's say in a non train.

Dr. Tresmaine Grimes:Let's see what I'm saying number one on Broadway. But it was there that I did not anticipate that Yale was in the process. Because I am of a certain age, this was a fledgling Afro American Studies program, with all of these intense black scholars who were arriving at Yale

Kandice Whitaker:to do this work. I mean, but are there any other type of black scholars, I thought intense was part of the description.

Dr. Tresmaine Grimes:And so what I'm saying to you is, I went there thinking that I would meet people that just didn't fit with me. And so I was anticipating, you know, the Macy's of the world and the gimbals of the world. And in that day, those would have been the jobs of the world and, you know, yeah, did not anticipate that I would have Toni Morrison as my freshman teacher, I did not anticipate that I would see and tussocky Shawn gay do the dry run up For Colored Girls who Considered Suicide. While I wasn't. I did not considered those things that in the binary key book library, you had slave narratives, I did not know. And so when I got there, I got there feeling like one thing would happen. But I wound up learning so much more about me, and about my culture, and having Sylvia Boone teach me Black Women and Art and having these tremendous musical experiences with people like that addley Jr, who was also there, at the same time, just so much richness that I didn't anticipate. So my worldview expanded by going there because I had an opportunity to not only take those classes, but again, because it was a fledgling program, you could still double major. So I wound up double majoring in Psych and effort and studies while I was at Yale who knew that would happen? And what I'll say is, when we come to another place in this conversation, the resources that were available there, were probably not available elsewhere. And so I think my worldview definitely got broader. I protested against apartheid. That wouldn't have happened. Had I not been in a space where I was around black intellectuals who were talking about our institution, investing in a Aren't those conversations were, you know, confronting us as students on scholarship? Where's the money coming from? Well, they're investing in South Africa. And we need to talk about that. Because when it come on here, episode

Kandice Whitaker:of a different world, it might have been.

Dr. Tresmaine Grimes:Yes, it was. But it was real. But it was real, was investing like all of the major institutions. And so we as students of color had to come to a place of saying, but we don't want that money. Because you're killing us to pay for us. So we're world view, you expanded in tremendous ways by being in New Haven, Connecticut, at Yale University at the time when I think it was in seventh the ish, that most black students, they started the whole affirmative action thing. And I came not long after they painted three Bobby seal on the wall. Because New Haven was that site of activism. I'm old enough to have been there, when it was the right time to enfin. So it changed my worldview for the better. It helped expand my understanding of blackness. It helped me understand the diaspora. The resources that were there were phenomenal. Don't ask me what it's like today. Because that was this was a different time. This was I'm not ashamed to say 70s. Baby, graduated in 1980. It was a whole vibe, then a whole different place. And so I am grateful that I had the opportunity unexpected. I did not expect Yale to trigger my blackness, but it did.

Kandice Whitaker:Like, we just need to see a lot it was a whole lot there.

Deron Hogans:That was amazing. Yeah. Well, let me let me try to answer this question before I lose it. Because as as, as she was explaining how she came to her worldview, is heard and felt a lot of familiar things. So I was trying to figure out why everything she said sounded so familiar. And I landed at a place where I could actually explain it to y'all with a short story. So I'll just tell you this story. And I think it'll answer your question about how my experience at Hampton, Anna Georgetown, for my worldview. So back in like 2010 through 2012, my primary residence was Harlem, USA. I spent that time in Harlem as an intern, baby. Yeah, working, working as a brand strategist at these advertising agencies in New York, one of which was on Madison Avenue. So classic madmen experience that I was able to have there. And so you know, so thinking about hearing about Heartland it just reminded me all the days that I you know, had to spend my morning and evening on the to train getting off at 116. And walking up down Adam Clayton Powell Boulevard and shout. And so and so just being being there was, I think, worth forming world framing experience, world point of view framing experience for me. Because let me tell you, I'll the only reason why I was there was because I have to. And the only reason why I was in New York was because a dean at my school of journalism saw a very distraught young man who had just gotten a degree in broadcast journalism, realizing that his degree probably wouldn't mean really much out in the world after having worked three internships, that TV news stations, and recognizing that coming out of school, he was probably only going to make at best $30,000 Being a production assistant in the middle of nowhere somewhere in America. And that was just something he couldn't do. And so she talked to me about my experiences about my skill set and what I wanted to do and what I was interested in, and she recognized that I was very interested in the arts and creativity, but also trying to use those things to have real impact in the market in the public sector in the private sector. And she said, Hey, why don't have you ever thought about working in advertising? And I was like, Well, no, I have never considered it. And she got on the phone and called another Hampton alumnus, who was in New York working at Yoruba cam, the ad agency and said, Hey, do you have an internship open? Because I have a young man here who I think would be great for it. And he said, Yeah, sure. Do it. And I was in New York the next week. So I ended up in New York, where I worked for three summers as an intern. And one of those summers actually got to take a trip a little further north to visit some family who I didn't know, I had never met. And my mom said, Hey, you're in Harlem, you're not that far. Why don't you just get on the train and head up to New Haven and me some of your world got off the train. And the first thing I saw was Yale. I never knew Yale was here, because not only did I get to see Yale, but I got to just see a completely different black experience that I had never seen before in New Haven. I mean, when they talk about the meccas of black people, I think of like, Washington, DC, you know, feeling in some ways, or you go out to Indianapolis, Detroit, these are really black places, right? But New Haven was just really black in a very authentic way, to the point where I think I met everybody in New Haven, in one day,

Kandice Whitaker:I think we did shout out to the home of the Amistad, New Haven, Connecticut,

Deron Hogans:I think I shook hands with every black person in New Haven that day, I think I hug every cousin I had. And it was just one of the most meaningful experiences of me, because I think all of the things that I had gone through at Hampton, as a legacy student, my mom went there as well, getting me into Harlem, having that network to support me at a time where I really needed it. And then it all kind of being aligned with family in a very strange, weird way. I think that shaped my worldview in a very, very strong way. I my approach to the world is like addressing it through my family. I when I think of activism, when I think of moving our people forward, when I think of all the things that I hear and see people discuss when they try to answer the question like how do we evolve as black people? How do we continue to achieve liberty? How do we make beautiful lives for ourselves? I dress it through my family, whenever I have maintaining relationships, proactively calling people checking in, what are you doing? Where are you going, how's everything, building those types of behaviors just to maintain connection, and then going to places to learn about people where they are in their lives, how things have been going to see what's happening on the ground, let me tell you, and often that I'll have a month, where I'm not on the road sometime in the month, where I'm going to South Carolina to visit family, I'm going to Norfolk or I'm going to wherever they are just to check in just to say hello. And then even beyond that, trying to be a resource in the best ways that I cannot. I'm not saying that I'm out here trying to like change anybody's life or anything like that. But if somebody needs a piece of information, if somebody has a question that they're trying to answer, if somebody has a problem they trying to solve my experiences that happen in Georgetown, and all these other places I've been have enabled me to do that. And if I have the capacity and the mindset to set it aside and help, that's what I do. And you know, I am involved in capital, I am involved in these other things that allow me to impact the community in different ways. But it always starts with family for me. And if there's somebody within my network, within my bloodline with my extended bloodline, or my extended extended bloodline, who I can make a connection with, and maintain it, and communicate with them and maintain relationship with them. I think I've done more for our people, then what I can do by picking up any any sign or going on any March or being in any museum, because there are people in need within our influence within our spectrum. All who all they need some sometimes just somebody to call and check in on them. And that's that's what I hold myself to because we're Dr. Bras Waitakere. All she did was make a phone call changed my life. Right? And so that very strongly influenced my worldview. And that's my approach to the world. It's like, what can I do by just picking up the phone and making a call, then that's how I try to move drawn.

Kandice Whitaker:I love that. That's a great thought.

Aaron Lloyd:What would you say would be the campus difference between a Georgetown and a Hampton just the day to day experiences of being on a campus? How would the energy different? Yeah,

Deron Hogans:this is a great question, I think because when I went to Georgetown, I was only a year removed from Hampton. So I was getting my master's. But I was definitely still within the age range of somebody who was studying undergrad as well. So I got to get the best of both worlds. And I think the biggest difference that I noticed being on those different campuses was the wealth of opportunity that was being offered to the students at Georgetown versus that

Kandice Whitaker:and so you share Dr. Grimes view. Hmm.

Deron Hogans:I don't think that we didn't have anything that happened. We definitely had resources. We definitely had a very productive career center that had a bunch of counselors who were there to help us figure our way. But at Georgetown, you got to think like Georgetown sits in the center of the public Medical Center of the World. And so you got all industries, all sectors all there on campus all the time. Deloitte, McKinsey, Bain Capital, Booz Allen Hamilton,

Kandice Whitaker:they are on campus got a house. That's right. Yeah. No,

Deron Hogans:I didn't even know what a Deloitte was at Hampton. And so that, for me was the biggest differences, just like the wealth of resources at the PWI. The other big thing for me was also just see and compare how black people engage with each other on campus. Now, of course, at Hampton, everyone was black. So everybody you talked to was black. And so sometimes looking back, I think I kind of took it for granted, because we were just so used to being amongst each other. But at Georgetown, I had to get used to being amongst others in a different way that I hadn't had to be aware of before. And then when it came down to interacting with black folk, it was almost like a secret society. Because I was like we were in.

Kandice Whitaker:I mean, that's the thing, though. That's how we raised Iran. Right, like, okay, white people around. Don't talk about that. Yeah, yeah. Well, you know, say that, but you get the look,

Aaron Lloyd:I know, in my experience, because I was in DC. So I understand what the Ron is saying a DC type of town where if the government closes, and the college closes, the city is closed, because I think the government might be the number one employer how it might be number two, you know, but you know, between Georgetown and American, but what I found, and what we found on how with campus is Alonzo Mourning and a lot of black kids from American, Georgetown and UDC even even though that's a black school, but these other schools would come to our campus, if they were black. They came out with campus for a social aspect to a party, that things of that nature. Now the grad students, I don't know if you would add them on to just get your work on. But I know the undergrads, they definitely they came to our campus

Deron Hogans:or how many times how are students will hop on their bus to come to Georgetown? Oh, my God, the weekend, we will have our black parties. We used to have like a black weekend, all the black people from all the different schools will come together. And that's why I say like, that was different from me. Yeah, it was, it was like we had to plan it. You know, like under wraps like, okay, like we don't go, here we go.

Kandice Whitaker:But I want to keep you out of this as a parent. When I was taking my oldest to go look at colleges. We want to go look at Georgetown right. Now. This is after we had been to Howard and we'd been to a lot of other places. Yo, Georgetown made me want to go back to school. They was like we have 100% job placement. Wow. Yeah. Oh, reps that. That's the reason that's what I'm saying. Yeah.

Dr. Tresmaine Grimes:It's the resources that's distinguishing. I gotta say this real quick, because you you just triggered me to run. The thing about Yale was just like Georgetown, it was not exclusive to the blacks in the school, so that we were really focusing on the black community, not just the blacks that yet. And it seems to me that that's what happened at Georgetown to being in that environment triggered something where you were more prone to look for black people, regardless of where they were being educated, even if they weren't being educated. Because at Yale, you had the Afro American Cultural Center, which was the hub for our what we called the house, shout out to the FM house by everybody, not just for Yale students, but for the black community. We did our tutoring there of students from schools in the area from Wilbur cross, I used to tutor kids from Wilbur cross as my work study. We had the Yale Gospel Choir which I sang it, which sang in the community and we went to black churches to sing. In fact, I own Yale Gospel Choir for the exposure to black churches that led to my exposure to one preacher in particular, the first black woman preacher I'd ever seen, which ultimately led me to join her church. When I got back home to New York. She was assistant pastor, but I came there for her that she had come up and preached and I was like, I want to go where she's at, which led me to preaching myself and now ultimately pastoring so I owe Gail gospel choir and the black church at Yale, but the exposure to the community in New Haven to all those churches that I went to singing that fed us that y'all got to stay and eat, and they loved on us, you know what I mean? And so The house was not just for Yale people, it was for the community. And in fact, someone that I still know, that was never a student at Yale, I met at the house, because she came through during her youth to be with all of us. So I get it to run, there's something very special about that atmosphere that we're not expecting as black students. But it happens. I

Aaron Lloyd:wish that was the case at Howard. And we had definitely had community outreach. However, it was an abrasive relationship. If you've watched school days, that's real, that conflict between the community and the college is real, especially when our campus is surrounded by an impoverished community. And you have from generation to generation that let's get a paper bag test. And you were an elite group of people that went to school in 1910, but not in the 1980s. We just as poor as you, we just happen to get to school. But that generational belief that's passed down through the years doesn't change. So you know, we were met with hostility and violence and conflict. And we still went out and volunteered in the community and tooted and did those type of things, but the energy towards the campus and the school was negative, not to mention, you know, not so much when I was there. But later on the university bought up a lot of property in the neighborhood. Also, you know, I don't like what Columbia is doing in Harlem, but really is how we're doing in around Georgia Avenue. Is that really any different?

Kandice Whitaker:What I was doing in New Haven? Change the name of the city? Yeah.

Aaron Lloyd:So I wish that was the case. You guys have me wondering about what level of opportunity Howard had. It definitely wasn't Georgetown, and definitely wasn't 100% We weren't tapped into Congress. I have a good friend net, who will remain nameless and work for US senator. And that Senator basically told him, you know, you can go to any law school you want in my state, as Senator went on to do some other things. And you know, him pretty pretty well, on average, well, as you can know, any politician did so there was opportunities and we would tapped into Congress and things of that nature. I don't think it was anywhere in there. Georgetown, if you were the best of the best that I would, there was plenty of opportunity for you. Business, whatever. But the average student it sounds like the average student at Georgetown. Uh, yeah, what's gonna be okay,

Kandice Whitaker:that's the main difference. I'm gonna put a paper clip right here. I'm loving this conversation. But when we get back from this break, we're going to continue and talk about the alumni networks. We'll be back. All right, y'all, we back into Happy Hour lounge. This is your girl Candace with a K. I have my co host today. Aaron, y'all know him. And then our guests, Dr. Tresmaine Grimes and Deron Hogans, and we're talking about HBCUs versus PWIs. So I want to ask our folks in the lounge today since graduation, have you taken advantage of your alumni network? And if you have what what does that look like?

Deron Hogans:Well, I'm happy to share I think I shared this in our initial question. But, you know, my engagement with the alumni network started immediately after I graduated with a direct referral to an internship that pretty much shaped my career since then, since then, I have taken on the role as the the alumnus, and there are there have been countless young people who have come to me over the past 10 years or more in my career, for guidance and feedback on how to break into my field specifically, which is user research and user design, or human computer interaction. And it's a space where you typically don't see people who look like us. And it's wedged within the design industry. And so there's various specialized experiences that come along with trying to make your way in so I've mentored countless folks review Countless portfolios, Review countless resumes, done, you know, fake interviews, mock interviews. And even more than that have just been like the guy that they call sometimes just to have to get some questions answered. So that's been my experience with the alumni network since leaving Hampton. And it's, I would probably best phrase, this like a cycle, you come out as the recent alumni who's, you know, looking for guidance. And if the Lord wills it, things go a certain way, one day, you become the mentor, and you are able to pay it back in, in time, and in, you know, help bring other people along on on the journey as well.

Dr. Tresmaine Grimes:I would have to say, Devine, I admire that I have been much less involved with the form whole network, although there is a yellow Black Alumni Association, I have not been very involved at all, I've gone to a couple of zoom events, honestly. And with the society that I'm a part of there, I have not been involved very heavily at all, think I went to one event that was just about time, not about desire. But in terms of Black Alumni from Yale, I've been much more involved with them than I have with the official network. So there are people that I still know today that are part of that network, they will be friends for life. And that's that, you know, so I admire you for being much more intentional about working with the mentoring of the next generation, that

Kandice Whitaker:is what it's all about. At the end of the day, I really believe as a community, that is how we're going to grow, develop, we all have to reach back and help folks as the folks in church was saying, you know, labor in any yo section at a vineyard. Let

Aaron Lloyd:me ask you, do you think that structurally, because of the inequities that black graduates face, that our alumni structures can be as powerful because obviously, the alumni aren't giving back the money that PWI alumni are, in particular, major football schools or Ivy League schools, but you don't see that in black institutions? And I suspect it's because they don't have the money on the same level nor the number of people. But do you think we're at a deficit in terms of giving money? And also building that network? Because are we in positions of power to really help each other? I

Deron Hogans:do think the HBCU alumni are given back to their schools in different ways. I think the question of like, the value of the dollar, in that case, you have to consider contributions from alumni across the board, right? So we look at HBCUs what folks will say like, okay, the alumni contributions are under a certain percent in comparison to what and if you compare it to colleges and universities as a total group, rather than like, pulling HBCUs aside and then comparing, it is smart, actually on par. So the money is contributed by alumni in HBCUs, are actually on par with the rest of the university universe. I think the issue is, we at HBCUs are much more reliant on alumni contributions because the endowments that we get as universities are much smaller than the ones

Kandice Whitaker:that make on it is the endowment. So

Deron Hogans:because we are much more reliant alumni are forced to open their books in strange in alcohol, I'll say like, in some cases, perverse way more perverse ways, then their counterparts at PW wise. So the resources are there, the money is coming in, but it's just because we are so the schools are so reliant on alumni dollars for their operational costs. But

Kandice Whitaker:Deron you said, proversed that's very specific. Why did you say that? Well, it's

Deron Hogans:just like, you know, you I'll use this as an example right? It's if you go to a new church, and I've been to before you enjoy yourself, the sermon is great. The Gospel Choir is singing great. And then you think that you bought to leave you know, had a great experience as a visitor, and then those doors close, and then the bucket comes out. And then they say, All right, the door

Kandice Whitaker:close you stupid.

Deron Hogans:There's a love offering and you feel forced to contribute your

Kandice Whitaker:love. Yeah.

Deron Hogans:That's why I say proverse because sometimes you know, you want to go back to homecoming or you want to go to the graduate One day, and you just want to like reconnect. And then next thing you know, somebody isn't passing around the bucket. That's why I say, proversed,

Aaron Lloyd:it's in a forced way where it doesn't feel like oh, you know, I give, you know,$100 to my school every year or whatever. But,

Kandice Whitaker:gentlemen, I will submit for your consideration aside from HBCU world, right? What happens in college, I think people very often pull on the experiences that they are accustomed to, right. It's the person who works in corporate, I can always spot the church kids. Because there's certain things they say, there's certain things they do, how they show up in the world, as a church kid, I was abused, y'all know, I went to church every day, almost church, kids are different. So like, I would submit to you that pass in the bucket, wherever you may be, whether it be at the HBCU event at church, that is normalized behavior. So to them. It's not intrusive, I understand why a person would say that, like when you said it, I got it definitely got it. But I also think it is the perspective of many folks remember that it is in the black church, that that's where most of us got our training. Most of us. That's where our our first time speaking in public was. So when you hear somebody in the boardroom, and say, oh, and today, you know where they came from, you

Aaron Lloyd:see, like a political campaign raising funds.

Kandice Whitaker:It ain't wrong. I'm just I'm telling you where I think it came from. That's just my opinion. Yeah, I love to

Aaron Lloyd:run a breakdown of one. We don't need to compare this to pw eyes. It's not the same situation, not the same circumstance, we need to refocus our thoughts on how we view this situation. And I wholeheartedly agree, but I think it comes from the desperation that most of these schools are that part two, because that perhaps how is Morehouse and Spelman will be considered in great financial shape. Now, they may not feel that way to their mission. But if you talking about some school down in Texas, you know, in university, there you go, I'm sure they're hurting in a different way,

Dr. Tresmaine Grimes:you're hitting the nail on the head, because it isn't that I'm begging because I'm a beggar. I'm begging because I have a lot. And I have. And when I don't have an endowment, that will allow me to do what Harvard or Yale can do, or Georgetown can do, and say, Oh, you don't have to pay, I'll bring you here from the hood, I will cover your entire tuition, I will cover your room and board, I will even give you a stipend for books, come to my school. And I'll place you even if I don't really like you. It's good for my numbers that I place you in at least some kind of work when you're finished. So I can do that for you. And how it is on the other side going. I have no money for scholarships for this kid. I've got to beg for my alumni. So maybe I can get a piece of these kids to come, I will fund the top 5%. And the rest of them when they come we'll have to take out a bunch of loans, because they want to go to Howard, but they're not going to get the money from us because we don't have it. It's not because we're mean, it's not because we don't love you. It's because we don't have what those other folks have. And so blood from a turnip, Amman. The issue of inequity and disparity between these institutions is really something that I think we need to focus on. I'm begging because I don't have it. Not because it's a ritual not because it's a thing. I know I'm in competition with institutions that will give your child a full ride. And I can't do it. In fact, Harvard went to the make less than approach. If your family income is less than whatever it is, this year, we'll give you a full ride. That's how many of the people that I know whose kids were of age in that season, before the court decision, went to Harvard because they could go for free, because Harvard was gonna pay them because their family income was less than $100,000. And so ever good luck

Kandice Whitaker:qualified to get into Harvard if your family makes less than $100,000. You didn't have access to the classes

Dr. Tresmaine Grimes:did just like some of us did when we went to Yale.

Kandice Whitaker:I mean, lightning does strike in a bucket but Harvard just started accepting kids from public school. Understood,

Dr. Tresmaine Grimes:but under stands that there was this whole philosophy of, I can pay your way. And now that the 18 to 24 year old population is shrinking, everybody's after these kids, everybody is trying to get them. So a school that has limited resources, I just heard on that I have a grandchild who is getting ready to be a sophomore in high school, her friends are going to college, one just turned down Howard, because even though they got in, there was no money. This is the dividing line now where the inequity is showing up, that that big endowment is allowing those bigger schools to suck away. Some of our students, it's not because they don't want to try an HBCU. But because when Mom and Dad Look at that bottom line, and it says zero, versus looking at the bottom line, and it says loans, then we're in this competition, and I'm gonna say this and I'm gonna be quiet. You know, that's hard for me. When I worked in South Carolina State University, which is a land grant institution, HBCU, I went to Clemson University to do some work for the advanced placement exam. And I had never seen a land grant institution with a dairy and a farm. What does that mean? In other words, the land was granted by the State of South Carolina for the education of equal. South Carolina State's land was granted by the State of South Carolina to educate black people. Clemson's land was granted by the State of South Carolina to educate White people. And because there was separate but equal as law. Clemson looks a whole lot different from South Carolina State Plessy versus Ferguson. I think this is an important point

Deron Hogans:also, because the nature of the education for black people was innately from elsewhere. If you notice many of them land grant agencies, schools were granted for the specific purpose of teaching people, black people how to do agriculture, agriculture.

Aaron Lloyd:That's right, Booker T the Booker T model.

Deron Hogans:agricultural work in mechanical work. So they wanted us to learn how to tell the land and fix the things that we use to tell it that that was essentially it. And by committing the schools to these very narrow missions for many years, I mean, hundreds of years really, and most of these schools, that was the limit of what they were able to do for black people in terms of educating us, it wasn't until the 80s and 90s, where we really started to see some of these HBCUs open their doors for premier business schools, right, if that in itself was a delay and a lag. So now we're in 2023. These schools are just now getting to a place where they are offering tech horses to get school students into the tech industry, but we're about 40 years behind. So Roundup is initiated by and a result of the land grant strategy, limiting black education to these, you know, labor heavy blue collar careers and limiting our ability to transition over into like white collar business careers. And this is the result

Aaron Lloyd:to bring some facts to this argument. Harvard, which had the largest endowment in the world, according to Google, is$49 billion. How would universities university's endowment This is Robin, I'm rounding off the numbers $49 billion. Howard University is $1 billion. Langston University is$45 million. That's right to bring it home in reality since you mentioned Langston Kandice. So if Howard, which has a billion dollar endowment can afford to bring in students on scholarship, what does that leave a Lexton a man they're trying to keep the doors open at 45 million. You're basically trying to keep the doors open.

Dr. Tresmaine Grimes:Trying to keep the doors open and passing the basket because it's always desperation.

Aaron Lloyd:These are things that we're that we're dealing with here. Everybody's

Kandice Whitaker:making great points. I'm loving this conversation and the energy but when we get back from this break, we are going to continue more. We'll be back We're back in the happy hour lounge y'all you already know who's here with chillin, Aaron, Deron and Dr. Tresmaine Grimes, and we're talking about HBCUs versus PWIs, we've had a wonderful conversation about all kinds of things, alumni network, land, grants, money, passing a basket, all kinds of things. But at the end of the day, if it was your kid, your God, child, somebody in your family, what would you recommend HBCU or PWI,

Deron Hogans:my son, and I talk about this all the time, and I reiterate this, what I'm about to say to him all the time, wherever he wants to go, as long as it supports what he wants to do. And it's gonna give him an opportunity to do what he wants to do in his life at a very high level of achievement. I'm gonna support it, whether it's a visa, PWI, or HBCU. And as a graduate of Hampton, with a bachelor's and Georgetown with a Master's, I am fully confident that as long as he takes that approach, he will be good to go and support whatever he wants to do, whether it be one or the other. But one thing, I will not move up on his capital, he got to be a capital.

Kandice Whitaker:Great cream in the house. Gotta be a nuke, I agree with that position. To me, my conversation with my children is, you know, you have to pick a place that works for you. And whatever that means.

Dr. Tresmaine Grimes:I have to agree. It's got to be an individualized decision. Where is your child going to get the best help? Because all students need help? Where are they going to get the major that they want? Or the encouragement to do what they need to do? Because we're coming back to the beginning here? How did we all get where we got to? What did Turon say? Somebody saw something in him, whether it's an HBCU, whether it's at a PWI, somebody saw something in us, and they poured it in. And that's what we want for our next generation. As, for me,

Aaron Lloyd:I have a slightly different take, I would say all things being equal, meaning that the universities are because I agree with the previous two sentiments, providing that the universities are suitable for a child providing that the major is suitable, I would prefer that they choose a historically black college, the shortlist the top institutions, unless it's an Ivy League school. And in that case, if it's an Ivy League school, I feel like the opportunities, the life opportunities of ivy league school, would outweigh the cultural growth and personal awareness, because I would hope they would have that growing up living in my household anyway. So I would lean towards the HBCU. Because I think for most people, that experience is going to be life changing. So that would be my lien. But I also think that if you got into Columbia, Yale, Harvard, it's kind of hard to say, hey, no, go to Morehouse. No disrespect. I think the academics at black institution gets disrespected way too much. But just the opportunity that those schools are just too great to turn down. I can

Kandice Whitaker:understand why you're saying that. And it makes a lot of sense. And the elephant in the room is what Dr. Grimes was talking about a little bit earlier. We're comparing oranges to apples, right? It is comparing the resources like because we are going to be who we are us the season diaspora. It doesn't matter where you find us. We're going to be who we are. But at the end of the day, aside from your education, aside from what you learn in the classroom, it is the access to the networks, it is the access to them phone calls that get you into space as you otherwise wouldn't be invited to. Yo, this has been an amazing conversation. I'm sorry, I gotta wrap it up right here. Thank you. Yes, co host, Aaron Lloyd. We'd love having you in the lounge love

Aaron Lloyd:Kandice Love the invite Thank you for having me.

Kandice Whitaker:Thank you so much Dr Tresmaine Grimes and Deron Hogans we love you so much and to everybody for listening we love you for being here we out

Kandice Whitaker

HostTracie Randolph

HostElizabeth Booker-Houston

Co-hostJudge Erika Tindell

Co-hostNakia Young

Co-hostRev. Hermia Shegog Whitlock

Co-hostPodcasts we love

Check out these other fine podcasts recommended by us, not an algorithm.

My Mic Sounds Nice

Aaron - Kev - Tim

MProper Mimi

Mimi Jacks

Beyond I Do

Byron and Margaret McKie

Speak Your Way To Cash

Ashley Kirkwood